Extras Reloaded

Proposal for spectral deportation of extraneous persons by applying a photosensitive suspension

Team

↳ Nadia Kaabi-Linke (PhD) and Timo Kaabi-Linke (MA), Subdivision Circuit Bending at the Anthropological Institute for Metaphysical Studies, F/UBerlin, 16/12/02

Keywords

↳ afterlife, evidence, extraneous person, ghostly matter, paranormal activity, photography, psychic force, remote forces, specters, spiritualism, trace record, Victorian portraiture, Zulu

Source

↳ Present Elsewhere. 15 Invitations 15 Years, Edited by Rashid Rhana. Asia Art Achive, March 2017, pp. 117-133

Links (Download)

↳ Extras Reloaded – Dossier

The tale of the bishop’s celestial slum dwelling

Bill Jay, in an essay on the history of photography, told a story about photographer Eddie Adams. When a bishop died, he approached the Pearly Gates. St. Peter checked off his name and sent him to a small, cold flat in a rundown building in the City of God. As the bishop retrieved his keys, a rough-looking man appeared. St. Peter asked the new man’s name, checked his list, and then became much friendlier. He gave him a large place with a nice view. The bishop, feeling uneasy, asked St. Peter: After a life of following church rules, why did he get a small place while someone less virtuous got luxury? Peter said, ‘We have many good churchmen in Heaven, but this guy is a photographer. That’s rare here.’ In this story, most photographers end up in Hell. Is this a joke or a genuine risk associated with the job? Why is photography seen so poorly? Once valued for honesty, photography was praised for visual facts, but as it grew popular, it lost trust. People shifted to calling it ‘imaging’ instead of ‘faithful reproduction.’ Next, we’ll examine two cases where we utilized photography, analyzing our methods in light of the medium’s history and ideas.

#content

- The tale of the bishop’s celestial slum dwelling

- Dark matter in the light box

- Nausea of a supposedly savage warrior

- Modern visions on colloidal suspensions

- Silver bromide souls

- Conclusion for a photographic detachment of the extras

- Feasibility and ethical assessment

Dark matter in the light box

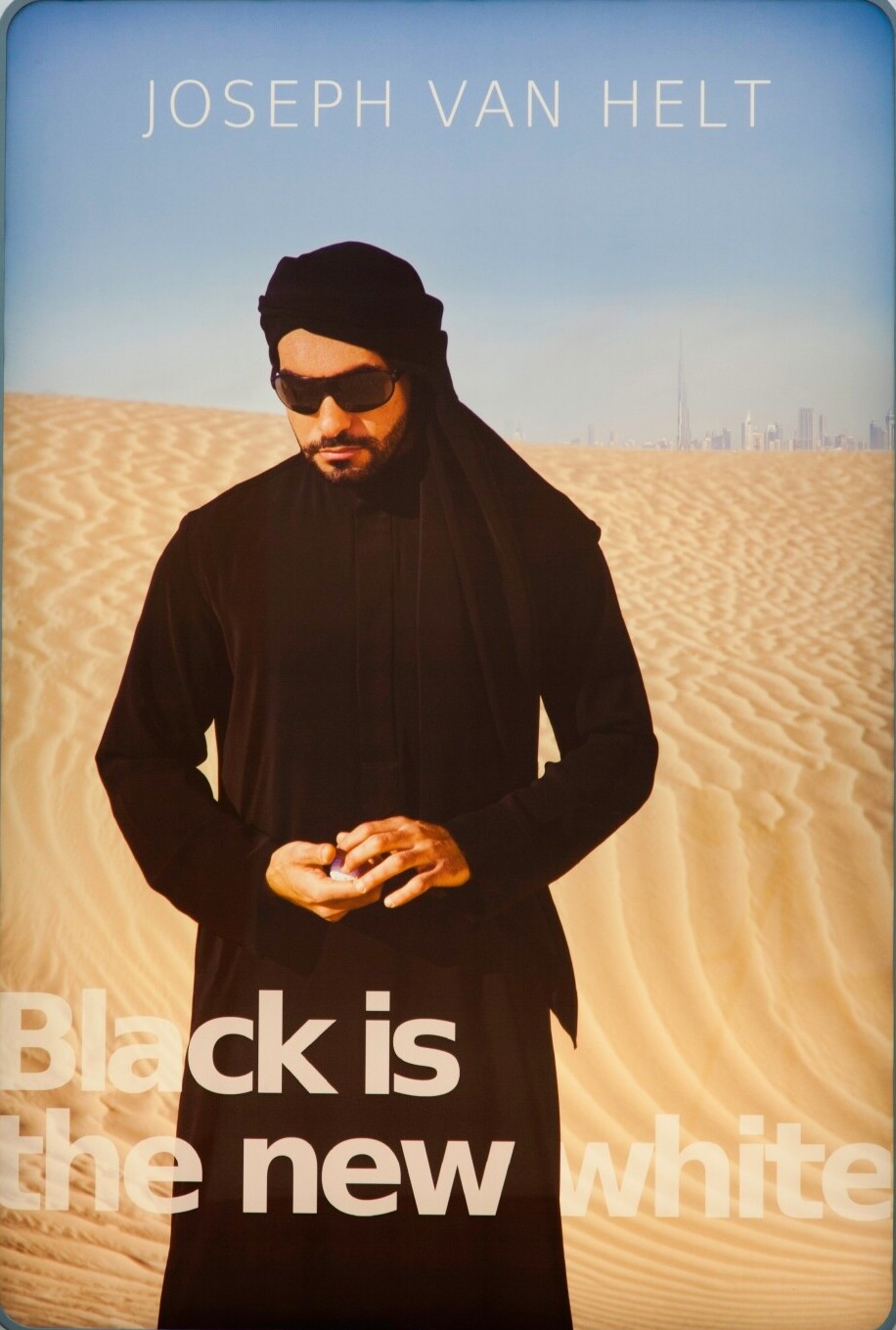

We used photography twice. Our first photograph, Black is the New White (2012), copied the style of glamour magazines. We did not reflect on the process; photography was a tool. Our goal was simple: to create an advertisement in a light box that disrupts local consumer imagery. We did not think about photography as a reproduction method. The outcome mattered most: a mixed image with regional codes that told of a displaced man. We used gender cues, location tags, and strange objects to spark viewers’ imagination. Nothing was natural; we altered every detail. The background, with Dubai’s skyline and a dune, was created. These places exist, but are not together—we combined several sites into one iconic view of Dubai. The man looks local, but the model is a foreigner. His clothes copy traditional styles; the fabric is from an abaya. The sweat on his forehead seems logical for a desert, but the photo was shot at 55°F. Our photographer supplied his own sweat, which we added digitally. The golf ball served as a visual cue—the model had to look down to show fake sweat, and the ball provided a reason for him to do so. Every part of the composition was arranged with no fixed message. The goal was to fuel the imagination.

We skipped photographic production issues and focused on arranging codes (visual elements with cultural meanings) and signs (symbols conveying meaning). References to the real world, like the skyline, sand, cloth, model, and other items, were secondary. The key was the meaning that arose from the entire composition. This message comes from pictorial codes and connotations (implied meanings), shaping how a photo, realistic or imagined, is seen. It is like dark matter: invisible, but still shapes how we interpret images. Roland Barthes raised questions about the photographic message. [1] His main issues are: How do we read photograms (photographic images)? What do we see? In what order? Can we perceive an image without labelling it with words? In other words, can we view the picture apart from its code?

Sidenotes

[1] R. Barthes, ‘Le message photographique’, in L’obvie et l’obtus. Essai critiques III, Paris, Seuil,

1982, p 21.

Nausea of a supposedly savage warrior

We faced these questions again in Faces, 2014, a portrait series at Cabinet of Souls, part of the Mosaic Rooms’ 2014 ‘Future Rewound’ show in London. The BITNW light box work prepared us for this. This time, we did not make a new image. We used a photo from the University of KwaZulu-Natal Library in Durban. The photo, over a century old, is labelled as ‘Chief of Zulus, his wives and troop of Zulus,’ like an ethnographic display. Looking at it, we felt uneasy. At this time, we were also researching the history of the Tower House, where the Mosaic Rooms are in London. We found that Imre Kiralfy, a Hungarian showman, was the first tenant. He ran London’s Exhibition Ltd. and organized the Greater Britain show at Earl’s Court. This exhibition promoted the Empire’s colonies and drew investors. The South African part showcased an Anglo-Zulu War performance, sponsored by the Chartered Company, which was owned by Cecil Rhodes, a mining tycoon who amassed immense wealth through strong-arming and lobbying. But the Cape Colony’s colonial office and London’s colonial secretary withdrew support, fearing the exhibition would misrepresent South African life.

At the turn of the 20th century, Rhodes had a poor reputation in London. He got blamed for provoking the outbreak of violence in the Transvaal region a few years earlier, since he was behind the digging rights to the land of the Matabele tribe. It came to an asymmetric war between Rhodes’s militia and native warriors in which many white settlers were killed. For this reason, it was no surprise that the main attraction from South Africa at the exhibition was a spectacle called ‘Savage South Africa’, produced by Frank E. Fillis, a circus performer and showman from South Africa. The event was strongly promoted in newspapers and exhibition guides as a faithful representation of ‘life in the wilds of South Africa’. These wilds were depicted in one of Feszty’s panoramas, which served as a background for 35 mud huts that housed 174 native South Africans, exported to London by Fillis on behalf of Cecil Rhodes.

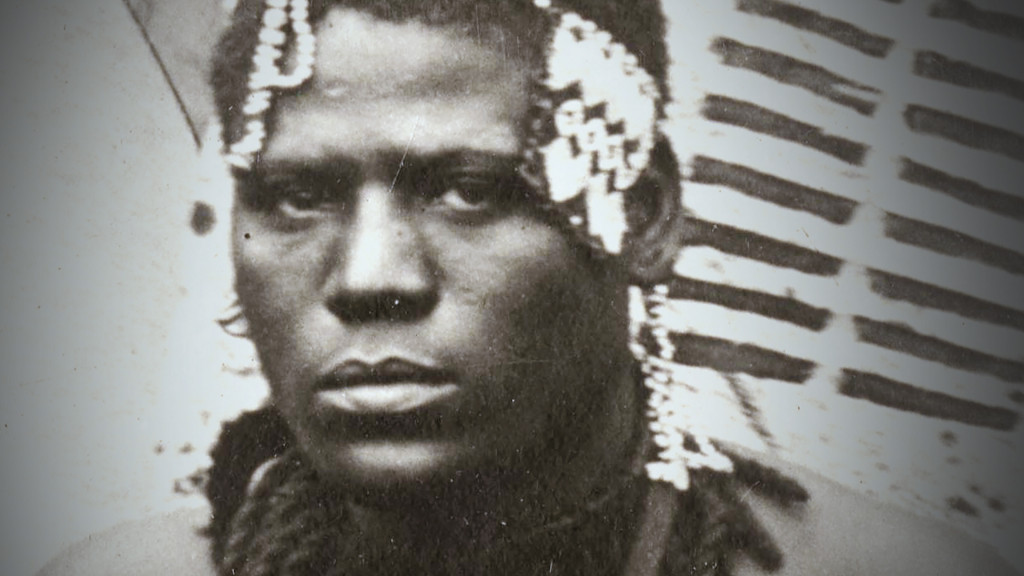

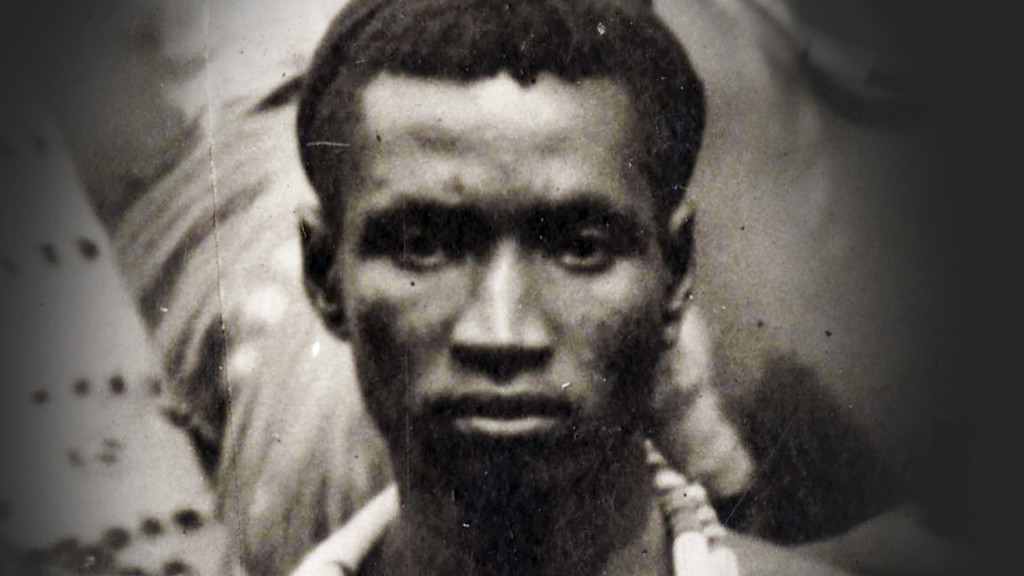

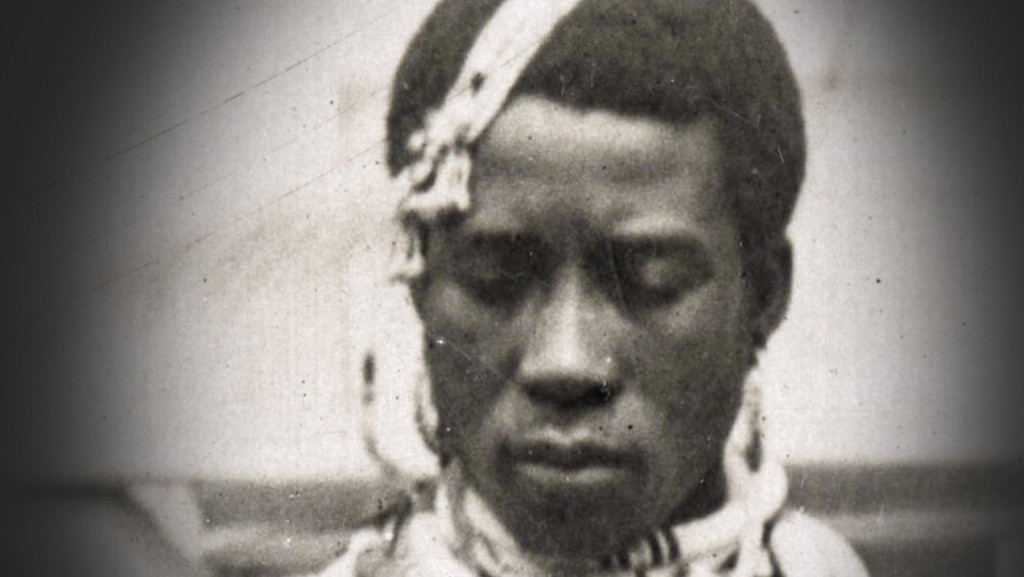

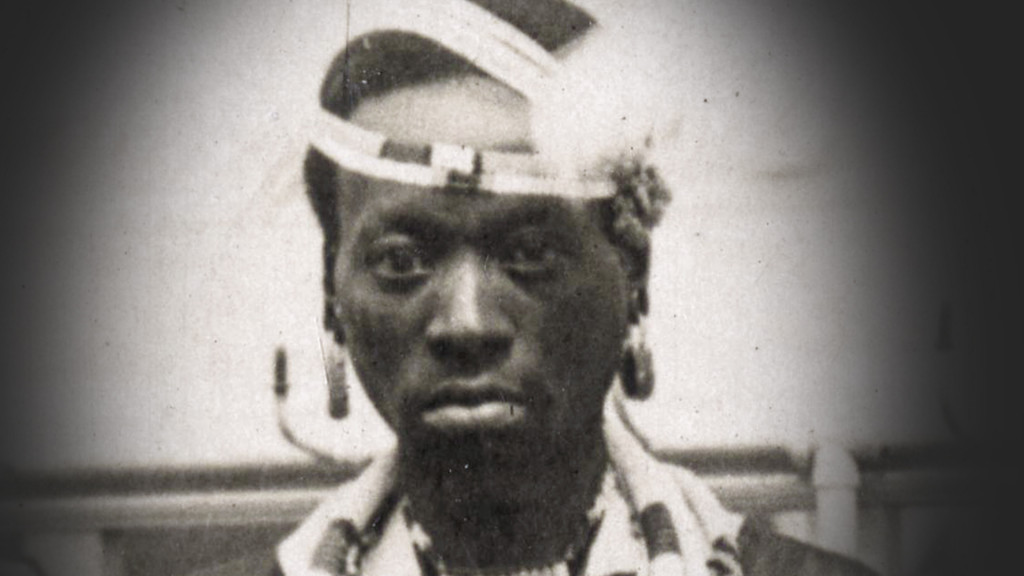

Keeping this in mind, we started to read the archival photograph quite differently. We examined the faces of the alleged ‘warriors’ closely, using a drum scan of the image that allowed for multiple magnifications. The entire scene was a perfect mise-en-scène; the extras were dressed as warriors, wearing shields and spears, and adorned with feather dresses. Though the costumes were not overly exaggerated, they were unusual for the Matabele at that time. Additionally, we felt that their faces did not resemble the faces of ‘savages’ at all. If one were to change their clothing, they could also be considered teachers, accountants, officers, missionaries, interpreters, and—according to the results of further research—this would better reflect what they actually are. [2]

[2] Valery Ward and Margery Moberly, two South African journalists, referred in 1999 to an archival photograph taken in the compound showing “a congregation of fully dressed South Africans hearing the prayer of an English priest.” Each Sunday morning, before the exhibition grounds would open, the exhibition organizers had to allow a service. This was a condition set by the extras of the spectacle. Ward, V. and Moberly, M., “The Travelling Circus from ‘Savage’ South Africa”, The Witness, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, October 19, 1999.

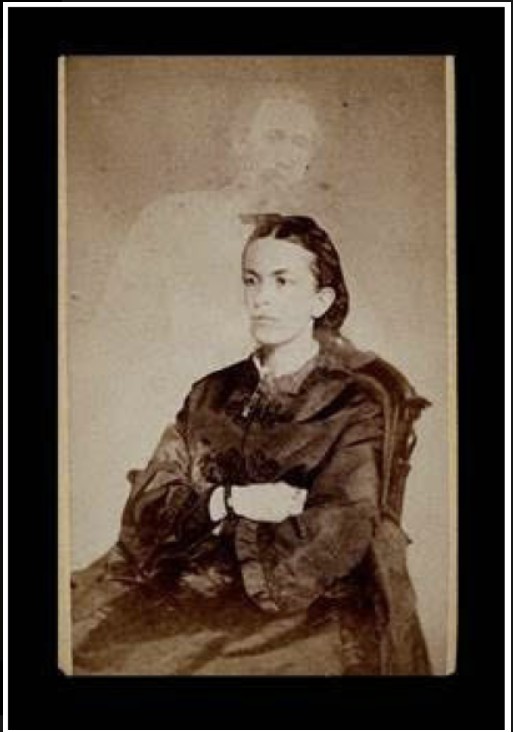

The close-up on some of the extras’ faces drew our attention to a curious look: some of them appeared to express seasickness. We found ropes and chimneys in the background, which led us to conclude that the image must have been taken on a ship. Further research confirmed our hypothesis: it was taken on the SS Goth, an intermediate steamer of the Union Line. The photo must have been taken before the steamer entered the harbor in Plymouth to provide visual material to the press in England for the announcement of the spectacle. After the facial expression of the seasick traveller attracted our attention, we also looked closely into the eyes of the other extras in the group photo. Finally, it was revealed that the entire scene had been a setup. This unintended expression was also part of the message, but it escaped the photographer’s attention. It is an unwittingly objective side note that was captured by the exposure of the plate rather than by the shutter-pressing subject of the photographer. Barthes calls this kind of semiotic side effect an ‘unsharp meaning’. [3]

It is not immediately apparent, like the well-composed meaning of an image, but it is also readable and understandable. However, it is not explicit and most likely an unauthorized feature of the image, but it cracks the shell of sensemaking and triggers curiosity for further questioning and interpretation. Despite the historical context of the Greater Britain exhibition and the signs that indicated the steamer in the photograph, when we found it in the archives’ catalogue, it was still labeled with the exact wording with which it was branded by Rhodes and Fillis in 1899. Both wanted the picture to be read as an example of South African savages. Although entirely constructed, it conveyed a very strong message that could even withstand the critical expertise of academic archivists. For this reason, we attempted to decipher the sealed meaning of the image through a photographic tradition that would help re-establish a similar situation, akin to examining each face on a magnified drum scan. Thus, we isolated each individual and reframed them in the style of Victorian portrait photography. In the past, many single-person portraits were created similarly, as a result of extracting individuals from family portraits. The typical oval frame was ideal to isolate a face from others. It changed the way the subjects were looked at. Suddenly, they began to resemble disguised young men and women.

By applying this method of face extraction, we could get closer to the individual character of each extra, but it did not eliminate all categorization and codes. We learned that in the Zulu religion and South African mythology, life after death is divided between the horizon of Samani, representing the eternal life of the soul, and the Sasa period, an intermediate world that is closer to actuality. It connects the living and the dead. In addition to this, a South African soul is site-specific—it is bound to the place where a person passed away. As long as the living remember the deceased, their souls would not be granted access to eternity. This would not have been a problem, since memory in Zulu terms is primarily an orally transmitted form of memory. As soon as the last friend, relative, or acquaintance died, would they be allowed to move?

However, most of them were baptised and educated as mission boys, and in Christianity—if one looks at all devotional objects and monuments—memory is obviously a materialistic concept. Since they were cultural hybrids of Zulu belief and Christianity, their souls must have gotten trapped in the suspension of the photograph taken on the Goth. As long as their faces would be recognizable in the group photo, they would be retained in the Sasa period and stuck between life and the realm of the dead. The photograph condemns them to a remote presence.

The work ‘Faces’ could attribute a kind of social dignity to the misrepresented extras, but it could not redeem their souls. In contrast, it even fortified their actual state of being by making their faces even more recognizable. By this logic, we need to address this issue by asking if there is a possible salvation of the extras at all. Seeking a conclusion to this request, we must revisit the history of photography and apply our problem to a kind of homeopathic solution. The issue caused by the photographic reproduction must be addressed through the photographic reproduction.

[3] R. Barthes, ‘Le troisième sens’, in L’obvie et l’obtus, Paris, Seuil, 1982, p 48.

Modern visions on colloidal suspensions

Going back to the beginning, the dead bishop did not fancy photographers, but St. Peter did. The acknowledgment of photography underwent a significant transformation, although its technical principles remained largely unchanged. While the optical mechanism in the camera was often credited, the anthropomorphism of the camera’s eye also contributed to an undervaluation of photographic reproduction in terms of visual objectivity. The success of a photographic exploration of a visual world beyond human eyesight was largely due to the photochemical emulsion that captures the intensity of light reflected or absorbed from objects in front of the camera lens. László Moholy-Nagy drew attention to this basic feature in 1927, stating that the photochemical emulsion, whether applied to glass, metal, paper, or celluloid, would be the fundamental requirement for any productive use of the medium, whether for cognitive or aesthetic purposes. [4] Until that time, the common understanding of photography was mainly linked to the optical aspects of the technique that reproduced the more than 500-year-old principles of the camera obscura. The main focus was on the way light masked the factual newness of the direct imprint of light onto the photosensitive emulsion. The photosensitivity of halide and bromide crystals is the primary reason for photographic evidence, as these reactions are triggered by light reflected from outer objects. Hence, every entity that connects to the cosmos via light can get printed in the emulsion.

Towards the end of the 19th century, the success of photography was undeniable, undermining the reliability of the human eye in terms of objectivity. It was applied in science and gained particular fame in anthropology and criminology studies. Eadweard Muybridge arranged twelve cameras in a row to show that galloping horses had a moment with all hooves off the ground—a fraction of a second that was unrecognizable to human eyes. No painter paid any attention to this detail; even Muybridge only discovered it to defend his claim and win a bet. The result was somewhat shocking; it was evidence of a fact that had never been observed, although it occurred regularly.

Another productive use of photographic techniques is linked to the name Francis Galton, a relative of Charles Darwin, who also became known for phrenology studies. His idea was the composite portrait for which he did multiple exposures of one or different persons on the same plate. Then he photographed the superimposed image to capture the resulting face. The final result was surprisingly successful and considered to have significant characteristics. It seems that they represented an idealized look of a person or group.

These composite images would become both birth and confirmation of anthropometric typologies. Galton became interested in particular generational and racial types, such as the Hindu and Caucasian types. With not much speculative effort, one could even claim that composite photography fostered the theory of descent. From anthropometry, it was a little step into criminology. Edmund DuCane, Director General of Prisons, supplied a series of portraits taken from murderers detained in London’s prisons. The shots were superimposed and reproduced by Reynolds, who specialized in scientific applications of photography. The idea was to identify a general ‘murderer’ type to help determine a possible murderer before they committed a crime. A temporal aspect emerged as prosecutors applied visualization techniques to predict criminal acts—usually, forensics functions in the opposite way.

Later developments in photographic techniques, utilizing infrared, ultraviolet, X-ray, dark light, and Terahertz rays, would extend our visual range far beyond the limits of human vision. All these technologies were developed and refined for one purpose: to deliver to the human eye visual facts that it was unable to detect on its own. This kind of image is different from those we are used to ‘reading’.

Reading the unseen image is impossible since no one ever learned to understand its language. Barthes calls these kinds of images ‘shocking’ since they bring to light a photographic insignificance and repel codifications and styles of representations. [5] In relation to interpretation, these images seem to be closer to the light of objective truth since they do not distract with cultural codes. Instead, they bypass our apperceptive capacities and reduce us to an undirected seeing.

[4] This is what László Moholy-Nagy brought to attention in his essays on painting, photography, and film. L. Maholy-Nagy, Malerei. Fotografie. Film, Leipzig, 1927. Reprint edited by Hans M. Wingler, Mainz/Berlin, Kupferberg, 1967, pp 26-27.

[5] R. Barthes, ‘Le message photographique’, in L’obvie et l’obtus. Essais critiques III, Seuil, Paris, p 20.

Silver bromide souls

The history of photography is also marked by mysteries that highlight the psychic capacity to reproduce the unseen. Many examples are documented in the Vatican archives. Research on miracles, such as the Shroud of Turin, is a fragment of this media history. There are even attempts to explain this phenomenon with photographic principles. If this were accepted, the face of Jesus Christ would be the original exposure (die Ur-Belichtung), and photography would have started with a portrait. [6]

The second half of the 19th century was not only an era of the humanities, such as physiology, anthropometry, and psychology—sciences that primarily referred to the irrational aspects of the human subject—it was also a time for modern spiritualism. Starting with the occurrences at the Fox family’s house in New York in 1851, interest in psychic phenomena exploded, and only four years later, the number of spiritual practitioners in the USA had grown to more than two million. In the early 1860s, William H. Mumler was drawn into spirit photography by chance. The jewellery engraver and amateur photographer experimented with autoportraits in the studio of a photographer friend and discovered, on one plate, the apparition of what they called an ‘extra’ or an extraneous person. Instead of him, a little girl was sitting on the chair. He was surprised and showed the picture to his friend, who said that the plate was probably not well cleaned. A little later, he mentioned this occurrence in conversation without clearly noticing his interlocutor’s interest in spiritualism.

Two days later, he discovered the story, including the address of the studio where the alleged ghost was conjured, in several spiritualist magazines and newspapers throughout Boston and the rest of the country. He was shocked and decided to warn his friend, who owned the studio where he took the pictures. As he arrived, the studio was already full of sensationalists who subscribed to the waiting list for their portraits.

Since Mumler was interested in both photography and apparitions, he seized the opportunity and started a new business and genre: spirit photography. Since he did not promise any positive results to the client, he was unsure if the apparition would happen again; he did not take any further risk, and by doing so, he was paid for the photography but not for the apparitions. Most of his clients had already been spiritualists before they came to Mumler’s studio. Some of them were even known as mediums. Mumler occasionally produced some ghost shots. He also attempted auto-portraiture again and discovered the apparition of a figure that he identified as his cousin, who had died twelve years earlier. After that, he bought out his friend to pursue spirit photography full-time.

One of Mumler’s clients was Abraham Lincoln’s wife, who wished for a photograph together with her husband. Mumler became famous despite being a controversial figure. His careless, happy-go-lucky disposition did not protect him from failures that led to his trial for fraud. The showman Phileas Taylor Barnum, at this time mentor of the above-mentioned Imre Kiralfy, testified against Mumler. He hired Abraham Bogardus, the famous New York daguerreotypist, to fabricate an image of himself and the supposed ghost of Abraham Lincoln. This photograph was tendered as evidence in Mumler’s trial to demonstrate to the court how easy it was to forge spirit photographs.

[6] Note that there are also many mythologies that date the invention of photography long before the birth of Christ. One myth refers to a Chinese emperor who lived in 1,000 BC, and others date even further back to Ancient Egypt.

But who could tell whether this apparition of Lincoln’s ghost was a forgery or not? In the end, Mumler was found not guilty, since no one could prove that Mumler didn’t believe in what he was doing. However, the US$3,000 expense of the trial killed his business.

Barnum himself was an American politician, showman, and businessman remembered for his celebrated hoaxes. He was the leading figure in marketing sensations at this time, and—this is quite important—he did not invent the spirit photography that attracted an audience of more than 2 million. Furthermore, Mumler owed nothing to Barnum, and Barnum had no reason to blame Mumler for anything; he was not even a client. He probably felt threatened by a new competitor and defended his claims in the market of sensation

against the mysterious newcomer Mumler.

Towards the turn of the century, spirit photography became very common among middle-class Victorian England, where no case like Mumler’s fraud trial occurred. Here, it was the opposite. Spirit photographers were renowned persons with professional backgrounds and ties to either Oxford or Cambridge. The public

scepticism was also less aggressive, although the business of spectral portraits was productive. It was a totally different climate than in America, and the hype of the genre lasted longer. At the turn of the century, an underground market emerged that supplied easy-to-use tools for spirit forgery, resulting in a significant amount of fraud. Nevertheless, one must admit that academics and professional photographers often controlled pioneers and stars of the genre, and they were never convicted of fraud. In addition, many later-known spirit photographers initially stepped in after being hired to supervise the methods of other spirit photographers.

With all this taken into account, it is justifiable to assume that Barnum campaigned against Mumler to defend the value of his own hoaxes and spectacles. As we already mentioned, Barnum was the mentor of Kiralfy, who allowed the ‘Savage South Africa’ spectacle to take place at Earl’s Court exhibition grounds. He was not amused by it and even considered it a bad and unnecessary representation of the South African people. On the other hand, he did not reject Cecil Rhodes’s blood diamonds. Hence, the story of ‘Faces’ continues, and we suppose that it will do this until the souls of the South African extras are redeemed and allowed to leave the intermediary world between actuality and enter their remote cosmic eternity.

Conclusion for a photographic detachment of the extras

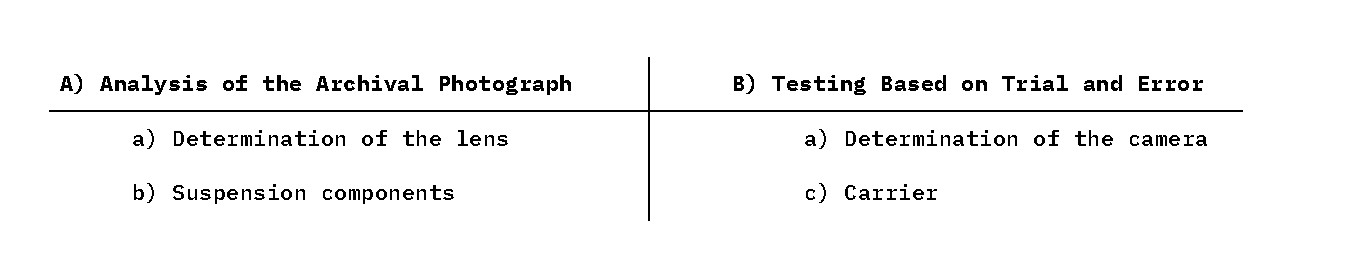

According to the African mythologies collected by John S. Mbiti [7] and Arthur Conan Doyle’s personal experiences with modern spiritualism, which involved journeying in Australia and New Zealand [8], the only successful method to redeem the souls of the extras sealed in the archival photograph would be to re-enact the original event. The reconstruction of the SS Goth steamer and the application of the same photomechanical appliances and methods would be mandatory for a successful outcome of this venture. To determine the originally applied techniques, we propose a procedure based on trial and error. The following steps, gathered in the table below, are mandatory for goal achievement: a) the finding of the appropriate camera and lens, b) the determination of the components and mix ratio of the original emulsion, and c) the carrier of the emulsion, either glass, metal, or paper. These findings will be brought to light by A) further analysis of the original photograph and B) by the simple decision-making based on trial and error mentioned above.

[7] J. Mbiti, Afrikanische Religionen und Weltanschauungen. Berlin, New York, De Gruyter, 1974.

[8] A. Conan Doyle, The Wanderings of A Spiritualist, Cambridge, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2009.

Table 1: Analytical and experimental approach to determination

Feasibility and ethical assessment

Photography is the functional exploitation of the physics of light. This makes the technique superior to the functions of the human eye, which are usually limited by physiology and refined by intellect. The chemical emulsion is able to capture visual information without any selective psycho-physiological relais such as the retina, optic nerves, brain, attention, perception, memory, emotions, or the censorship of consciousness. If one considers the velocity of light compared to the speed of human perceptions, it is quite clear that the difference between a visual object and its photographic reproduction would be insignificant.

Intuitively, we do not tell any difference between objects and reproductions—this is the reason why we collect photographs of our beloved. The difference appears to be made by the intellect, which is trained to respond to interactions and achieve goals. It is most likely that any facts in conflict with a socially successful behaviour are usually excluded from human perception. In contrast, light is an all-embracing cosmic energy, and its speed defines the limits of space and time. This is the reason why we conclude that photography, which utilizes the speed of light for pictorial reproduction, is the only reliable means of capturing spiritual facts that were never seen but always exist. Since light emanates in space and time and superimposes one on the other according to physical laws, it is our only medium for connecting with the remote and rewriting its past.

Pasolini always understood cinema as a medium of conjuring. It is essentially a transfer print of light emitted from outer objects onto a photographic emulsion. He never accepted that semiotic categories of cinematographic pictures would occupy more attention than their ontology. [9] Cinema shows the light that reflects from the objects onto celluloid as a raw image of the visible and invisible world without any rational or physiological filtering. It is a purely physical vision—a transmission of electromagnetic rays that immediately connects objects, eyes, and brains to the cosmos. By this understanding, Pasolini’s aim was not to compose a message and render an image readable to the human observer. He was rather after the image as such, the shocking image that would be its own message. These seemingly insignificant images speak to us in a language that we must first learn to understand. And we are obliged to do so for the sake of cosmological and spiritual integrity.

[9] P. Paolo Pasolini, ‘Essere è naturale?’, Empirismo eretico, Milan, Garzanti, 1991, pp 242-247.

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from Instagram. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More Information