“Blindstrom is a disruptive charge

that lingers in a closed circuit—

never fully consumed by the devices it powers.

It is what remains

when we believe we’ve let something go.”

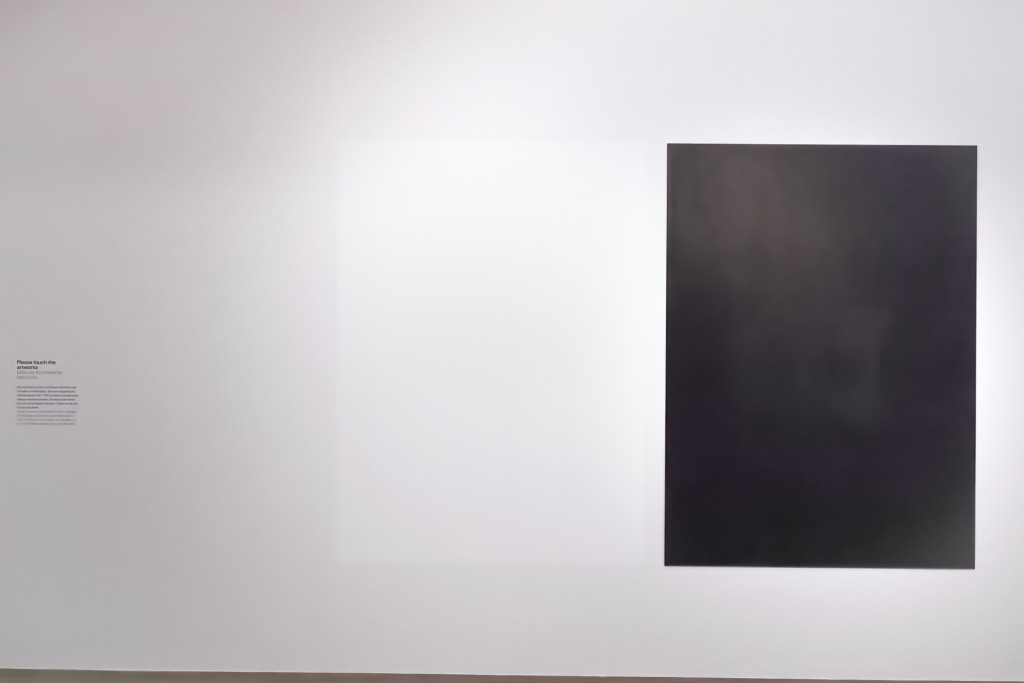

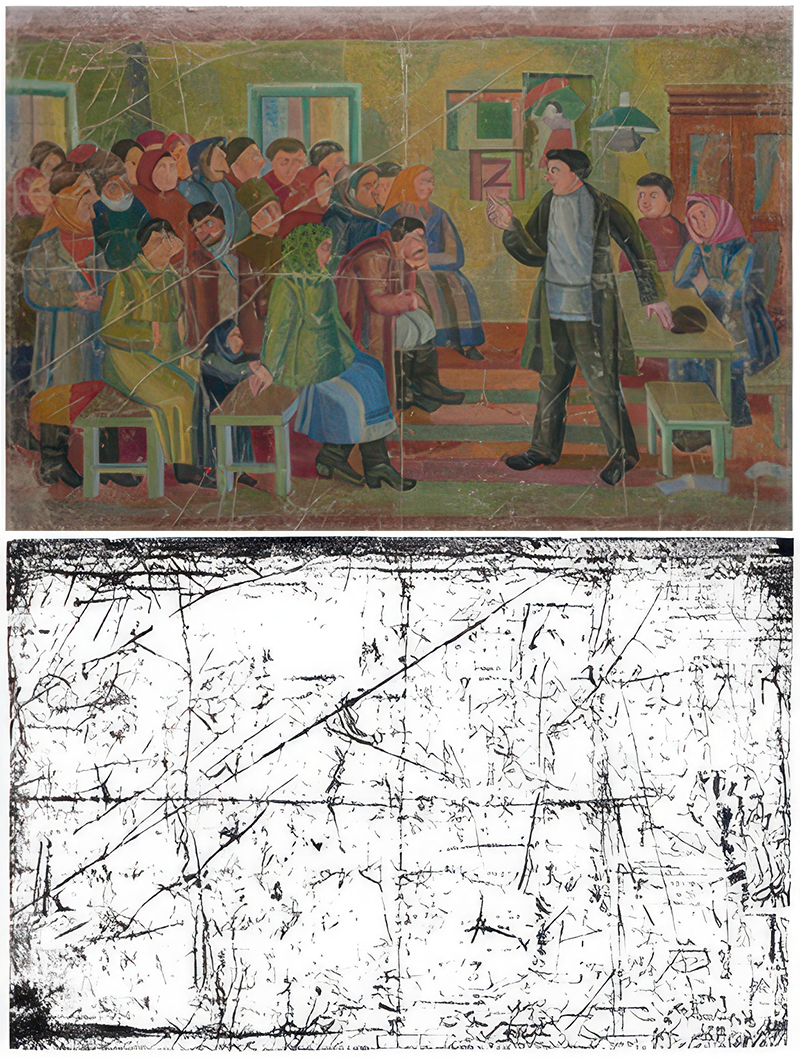

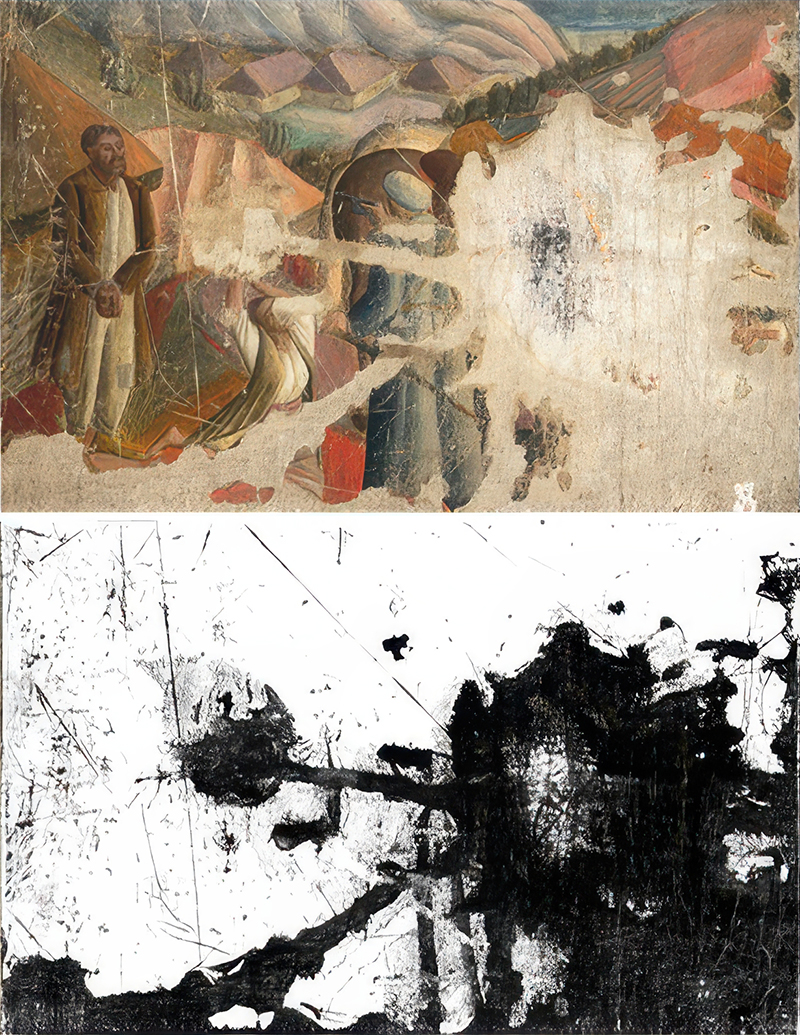

This installation features a series of paired white and black rectangles, arranged to evoke the minimalism and geometric abstraction of Kazimir Malevich’s iconic works, particularly his suprematist compositions. Malevich, who was born in Kyiv, Ukraine, is often mistakenly referred to as a Russian artist, a reflection of the complex historical and political narratives that have shaped the understanding of Eastern European art. His legacy, like that of many Ukrainian artists, was marked by state censorship, confiscation, and at times, the deliberate erasure of works during periods of political repression.

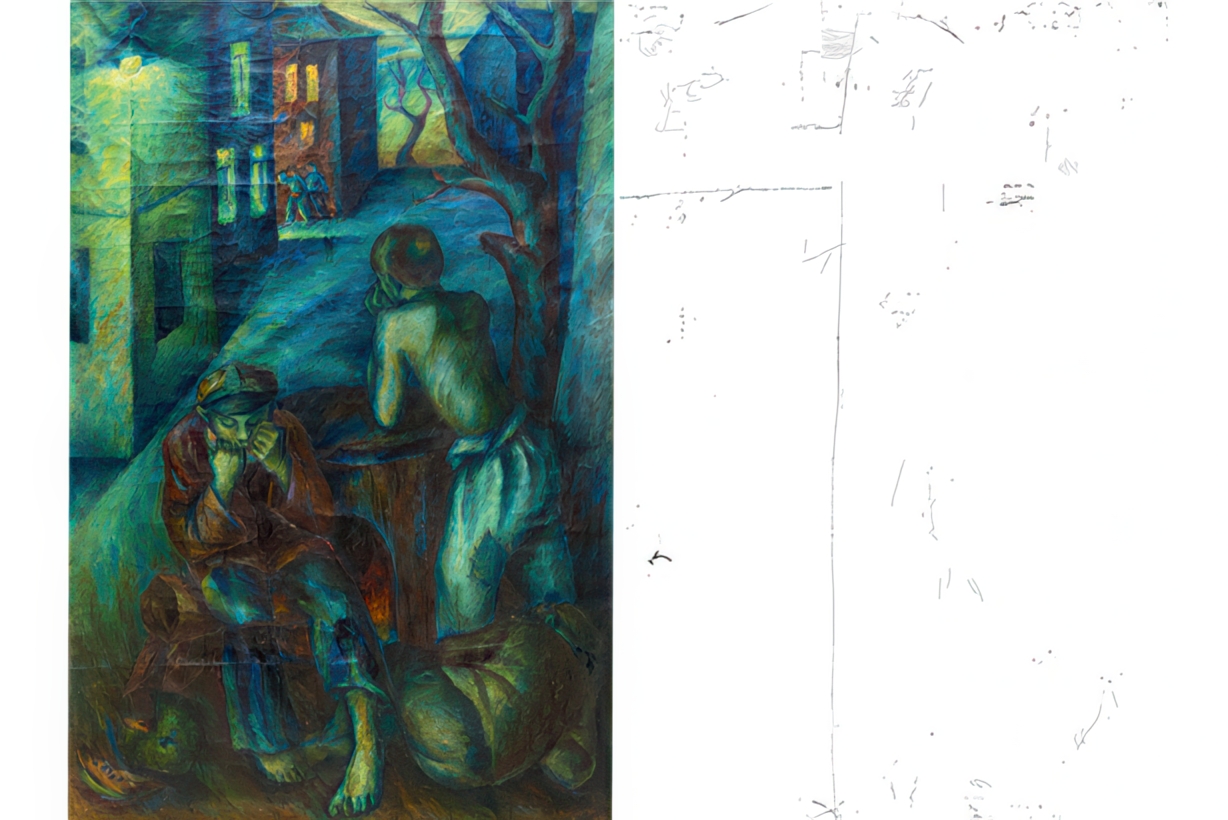

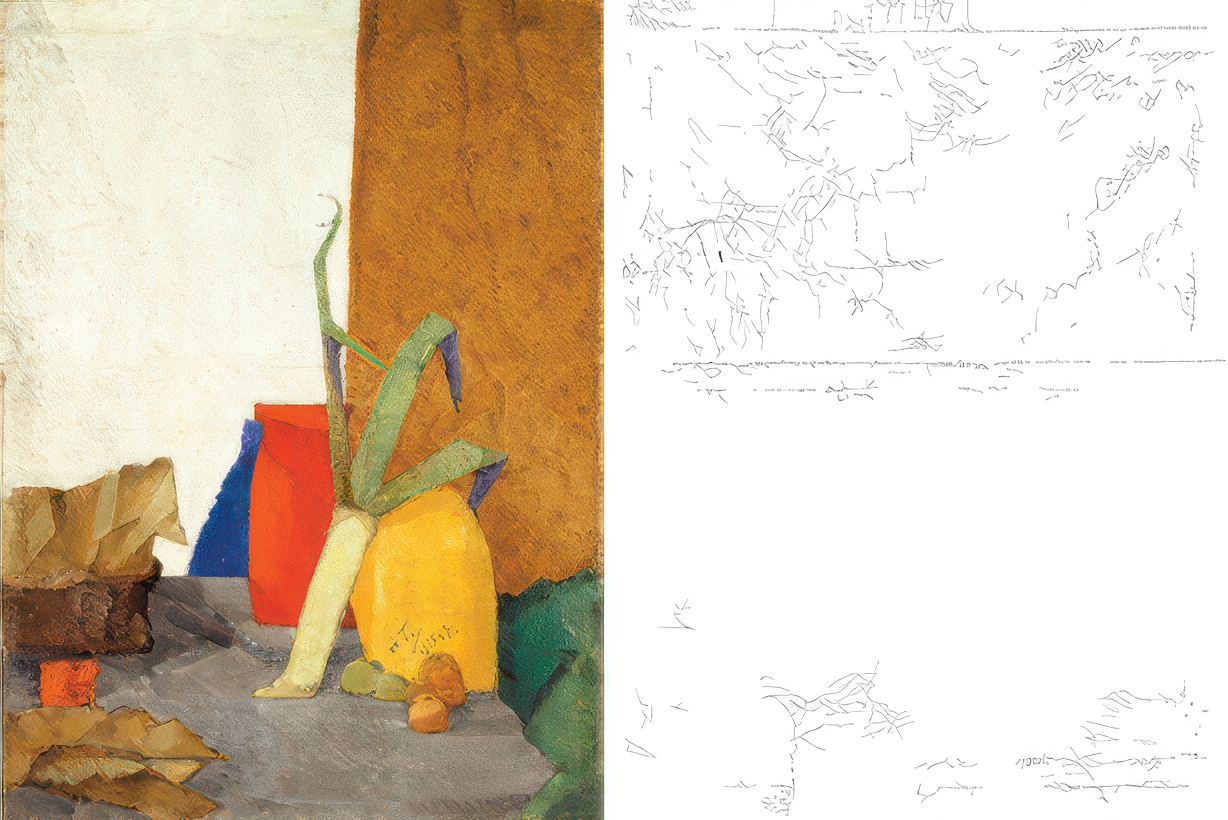

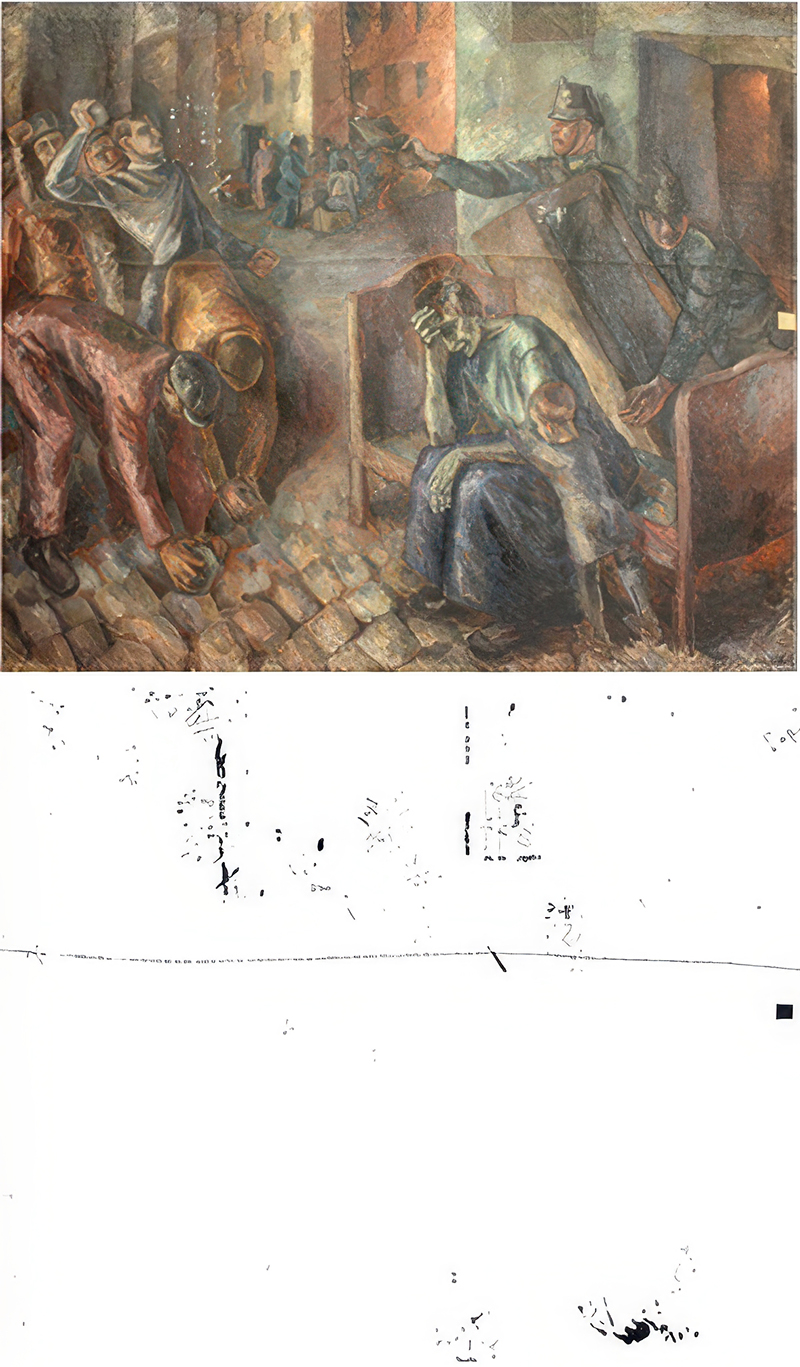

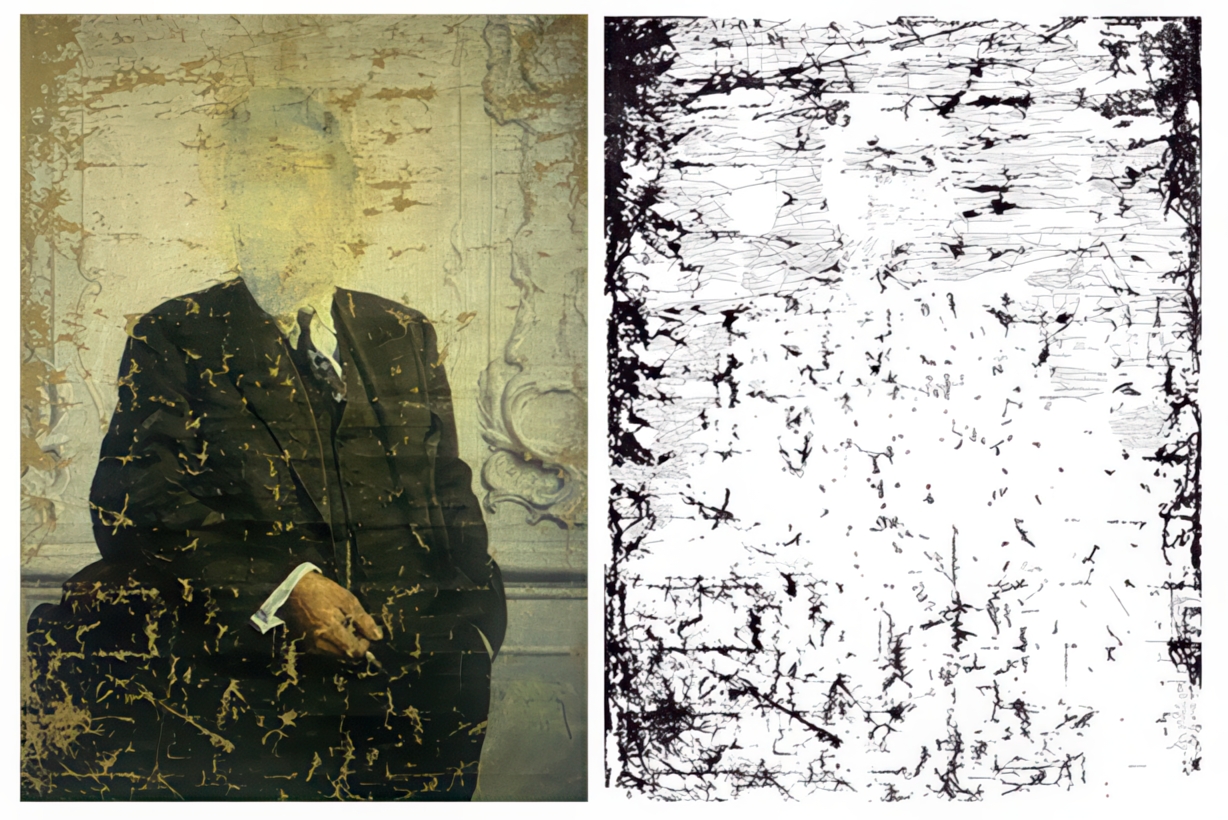

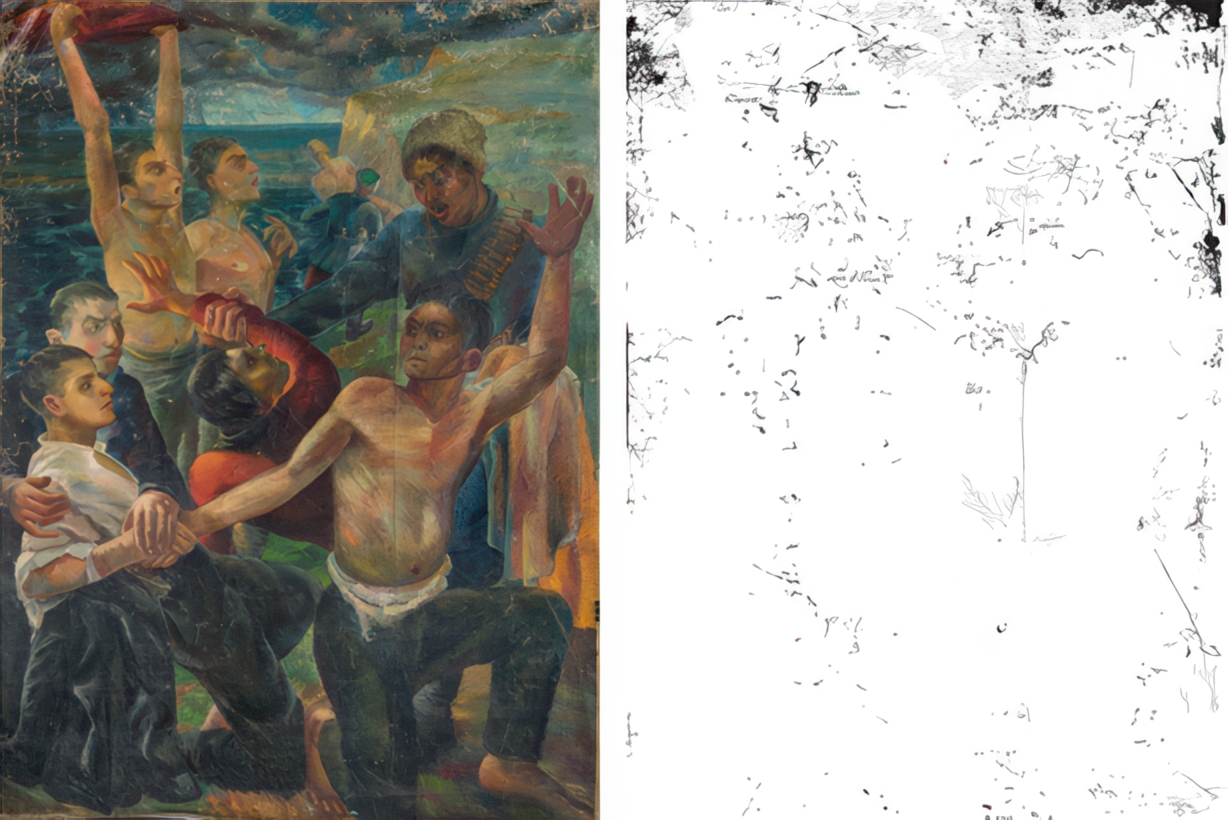

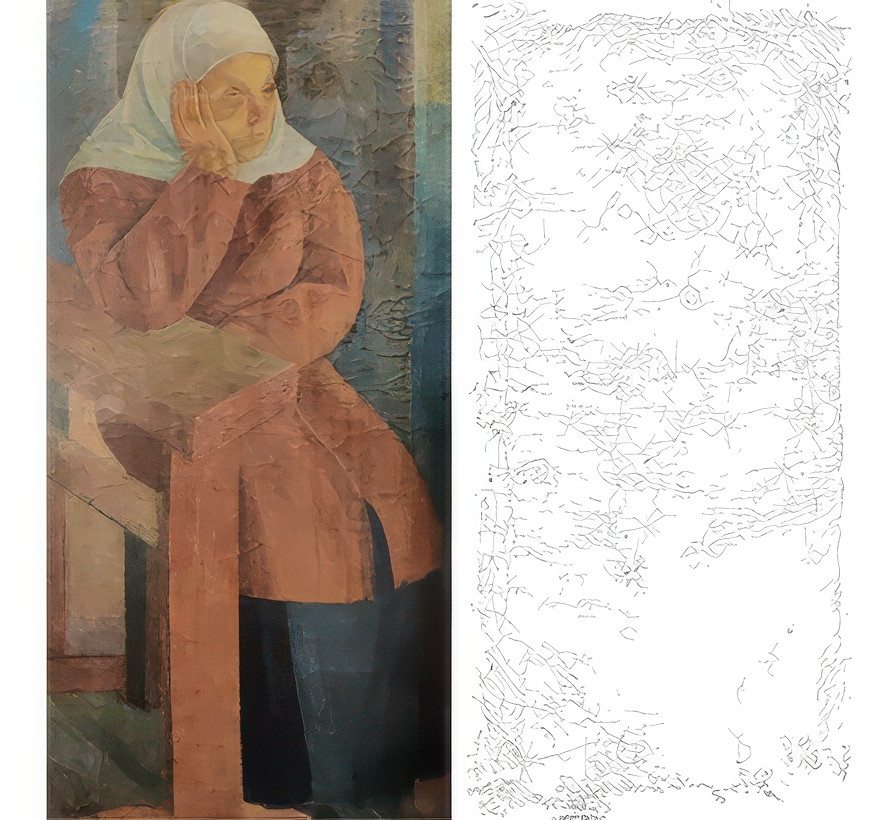

In the 1920s and 1930s, under Soviet rule and during the German occupation, many Ukrainian artists faced intense scrutiny, with their works being seized or destroyed. Malevich’s paintings, along with others, were hidden, confiscated, or even painted over during these tumultuous times. Remarkably, some of these works survived the Nazi looting and were later restituted to Ukraine, only to be concealed in a secret collection known as the Spezfond during the Soviet era. These works are now housed in the National Art Museum of Ukraine (NAMU).

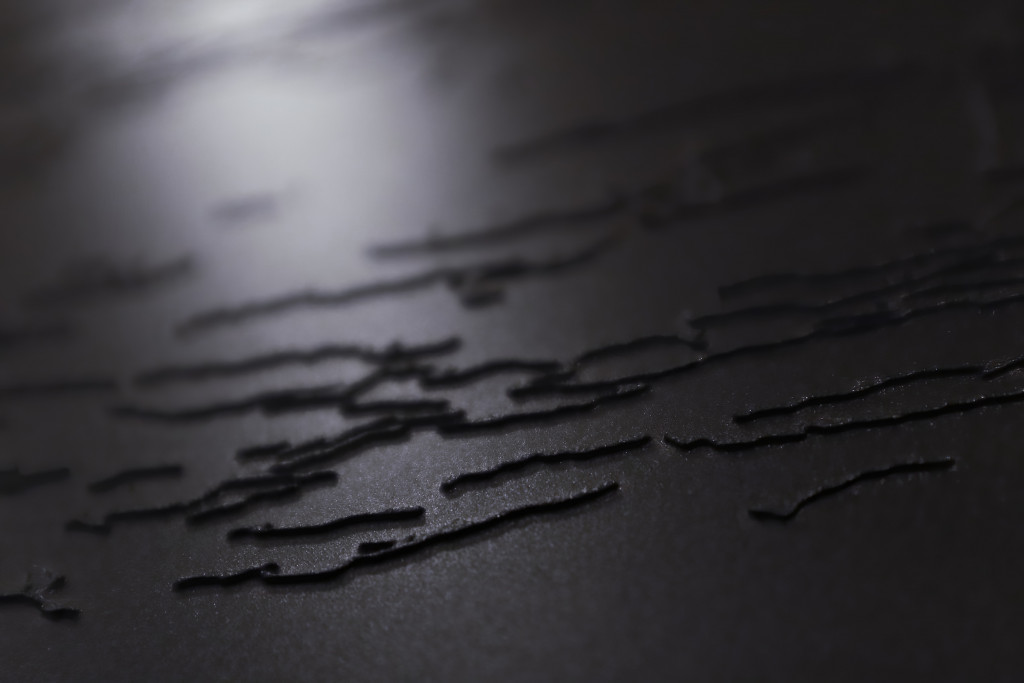

The artist of this installation references the historical damage to Malevich’s works, specifically the traces of abrasion and physical wear that occurred due to their turbulent past. The installation incorporates tactile black panels that capture these marks of damage. While some of the black panels can be physically touched, the accompanying white rectangles serve as a metaphor for the absence of the original artworks. They evoke the sense that the paintings once existed in these spaces but have now vanished, either physically or culturally, due to political erasure.

The installation’s minimalism and use of contrasting black and white rectangles not only evoke the visual language of Malevich’s suprematism but also serve as a poignant reminder of the broader history of cultural loss and suppression under political regimes. The white rectangles suggest a void, symbolizing the loss of artistic heritage, while the tactile black panels—inviting touch—offer a way for viewers to engage with the residual history of the artwork, connecting the present to the traces of the past.